World Mental Health Day – A Model for Wellbeing

The 10th October is World Mental Health Day, and to celebrate we should first reflect on how far we’ve come as a society. An increasing number of us are understanding the importance of our mental health and how it needs to be cared for with the same amount of attention as our physical health. Although there is a lot to be celebrated, there is still much left to do.

A recent study by UNICEF ranked the wellbeing of Britain’s youth 27th out of the 41 EU and other developed countries studied. Furthermore, due to the pandemic, the wellbeing of not only our youth, but us as a collective society, is on the decline. Therefore, the importance of understanding wellbeing has never been greater. Unfortunately, with a lack of consensus on a clear definition for wellbeing, it remains difficult for policy makers and school leaders to devise and implement programmes that might incorporate a greater sense of wellbeing in affected communities. This lack of consensus along with my own passion for wellbeing improvement inspired my thesis. The thesis aimed to seek out a model for wellbeing that could be used to provide parents and leaders with the tools and strategies to cater to the wellbeing of our youth. This is a summary of my findings.

What is Wellbeing?

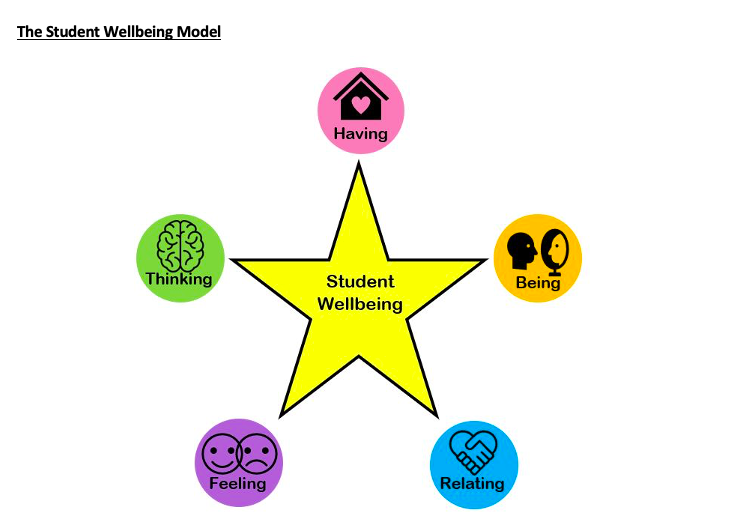

Mental health, wellbeing, welfare, these all largely refer to the same concept. Definitions of these range from the more internal definitions such as “a state of feeling good” to the more external definitions that discuss quality of life. It is becoming more apparent just how complex wellbeing really is. To oversimplify wellbeing would be like going for a check-up and the doctor telling you that your health is “bad” with no further explanation. Therefore, this is where the Student Wellbeing Model, a model proposed by a research group in New Zealand, comes in.

The Student Wellbeing Model

This model attempts to break wellbeing down into various sections that all contribute to a child’s wellbeing. Although the model is made with students in mind, the model really can be applied to anyone. Here is a summarised outline of each section:

Having

Having refers to a child’s ease of access to resources and opportunities, typically external to the student. Some examples are:

- Access to nature

- A sense of personal safety (we will come back to this when we explore bullying)

- Competent and caring teachers

Being

Being refers to how student’s experience and understand themselves. It is their ability to understand their own identity and how their identity fits in within their community. To support this section a school might implement strategies that encourage:

- Self-expression

- Student voice and democracy

- Recognised contributions to their community, be it school or the wider community.

Relating

Relating refers to the quality (not quantity) of relationships between a child and their peers, their parents, their teachers and anyone else in their community. It also includes how a child views the relationships teachers or parents have with each other.

In an environment that enriches this section, relationships are usually perceived to be:

- Reciprocal, not hierarchical

- Based on mutual learning and respect

Feeling

Feeling refers to a child’s ability to perceive, understand and express their own emotions. This stems from the area of research surrounding emotional intelligence or EQ.

Schools that have strong Social Emotional Learning (SEL) programmes, especially in primary school, tend to record students with much higher levels of EQ than schools that don’t. This is usually where you see schools discuss terms such as empathy in their values.

With a greater EQ, students are more equipped to understand and express their emotions and are less likely to turn to more destructive behaviours. It is actually EQ, not IQ, that has been stated to be a much greater indicator of success in adult life.

Thinking

Thinking refers to a student’s understanding of their own thought processes and their relationship with their learning. In a wellbeing promoting school this usually contextualises into:

- Student centred learning and student choice

- Activities that encourage a child’s curiosity and creativity

- Mindfulness (a student’s ability to regulate and accept their own thoughts)

- A strengths-based approach to learning

By playing to a student’s strengths rather than punishing their weaknesses we tend to find students with a much more positive outlook towards their education. Finally, by placing students at the centre of their learning and allowing them to direct the learning process, we tend to see greater levels of independence which further encourages students to take their own initiative, a very positive cycle indeed.

If these 5 areas have been successfully catered to, when we place students in challenging situations, we tend to find that students demonstrate desirable characteristics such as grit, determination and motivation. We also tend to find that students look at these challenging situations as positive learning experiences rather than potential threats, which encourages the type of positive and constructive thinking we try to impart in our students.

The creators of the model emphasise that the importance of each section is different for every person, and the same person might find that the significance of each section changes throughout their life. Therefore, as the model is constantly changing, we can’t just focus on one section, we must try and engage every aspect of a child’s wellbeing; the whole really is greater than the sum of its parts!

Strategies to Promote Wellbeing

Now, if the previous information wasn’t enough for you, through my research I found three key areas or strategies that had the greatest impact on student wellbeing.

Bad Behaviour and Bullying

Before beginning I would like to proclaim one thing:

Bad behaviour is a sign of poor wellbeing, not a bad child.

From low-level disruption to bullying to drug abuse, these are all examples of antisocial behaviour and are all symptoms of poor wellbeing. Unfortunately, the current way of dealing with antisocial behaviour (on both a school level and a societal level) tends to tackle the consequence, rather than the cause. There is a wealth of literature that support the notion that preventative strategies, like those that promote positive wellbeing, are far more effective at reducing antisocial behaviour.

What my research found was that if a child has strong relationships with their peers and their teachers, they are less likely to demonstrate antisocial behaviours due to a fear of “letting their peers down”. When someone is closely and positively connected to their community, they are more likely to strive to be their best self. That, in turn, creates a supportive environment where students feel safe and encouraged to be themselves.

So, let’s say you have ticked all the boxes and a child still demonstrates antisocial behaviour, this is bound to happen as we are all human. The most effective way to ensure that this behaviour doesn’t continue is not through punishment, but through restorative practice. Restorative practice is the process of sitting down with the child and providing the time and guidance to help them reflect on the situation.

“Is everything okay?”

“Why did that happen?”

“How were you feeling at the time?”

“What do we need to do now to make sure this doesn’t happen in the future?”

The aim of restorative practice is not to tell the child what to do or how to feel, but to help them arrive at the necessary conclusions on their own. Those who are familiar with coaching will recognise these techniques.

It may sound like a huge time commitment, but the time invested in restorative practice saves far more time in the reduction of repeat offenses. It also may sound counter-intuitive, but the positive and nurturing atmosphere of these sessions inspire a desire for growth in the child, unlike the cold and uninviting nature of the typical detention which tends to breed further contempt for the school.

Circle Time

The importance of healthy relationships between students and their peers and teachers could not be emphasised more. But how can we create an environment that naturally nurtures these positive relationships? One answer is Circle Time. Circle Time is the process of sitting together as a class and allowing students to discuss their feelings, their worries or anything that is happening in their life. Then we allow other members of the class (and yourself) to provide support and guidance regarding how the student might navigate this.

Circle Time is not a novel concept, but its importance is often overlooked. By allocating frequent and adequate time for a class to come together and support each other, we are modelling and nurturing the support network that we would like our students to have. Again, the incorporation of Circle Time is vital but not exclusive to primary school. Primary and Secondary schools that incorporate Circle Time into their curriculum record lower levels of bullying and antisocial behaviour due to students feeling that their voices area heard and understood.

Collaborative and Project Based Learning

Collaborative Learning is essentially what we have come to know as group work. However, it is not as simple as allowing students to work together on an exercise. By devising projects that work across the curriculum and providing students with the freedom to express themselves and play to their strengths and interests, we really see students coming into their own. Instead of teaching a lesson on compound interest, have students create a bank which has to explain interest rates to its clients. This could be in the form of a website, a video or a role play and it is important that the students decide how this will be presented. This creates avenues for students to be creative whilst still understanding the content. Not only does this create cross-curricular links, but it also answers the age-old “when am I going to use this?” question our students love to ask.

With everyone having a clear role and making equal contributions to a shared mission, this not only allows students to play to their strengths but also encourages skills that are so favourable in the workplace, such as being able to collaborate, take on constructive criticism and problem solve. These traits cannot be taught, they must be exercised.

Conclusion

A lot of strategies have been shared here that can impact every aspect of a child’s day-to-day life. Research has shown that for these strategies to truly take effect, it needs to be a whole school approach to wellbeing promotion. If you are a parent or teacher and feel that you might have little control over these aspects of a child’s education, there is a lot you can do. Use your voice to encourage schools to incorporate mindfulness, student voice and social-emotional learning into their curriculum. Schools with greater levels of wellbeing also report greater academic progress in their students, therefore these strategies do not distract from the curriculum but enrich it. A school is supposed to serve its community and if it isn’t, you have the right to demand more from it.

Finally, there are many small things that can be done without making huge changes:

- Schedule regular walks in nature

- Encourage yourself and those around you to allocate time out of their day to engage with their passions and interests

- Be the person that makes others feel safe to express their thoughts and feelings without judgment.

Children also look to us all as role models, so just by looking after our own wellbeing, we are demonstrating and instilling these behaviours in them. We really can be the change we want to see in the world!

Adam is a maths and physics tutor with Newman Tuition. To book a lesson with him, or one of our other excellent tutors, please call us on 020 3198 8006, email us at [email protected], or complete the form on the ‘Contact Us’ page.